This is because we must first carefully spell out the law-like statements that are made in the context of the table. Lastly, laws are conditional claims: if an object of mass m falls from distance r, then according to Newton’s law, it will hit the ground with velocity v.Ĭan we say that the periodic table satisfies these features? The answer is not as straightforward as in the case of Newton’s law. That ‘all gold conducts electricity under standard conditions’ is an example of this. Furthermore, laws are universal (or at least statistical) claims: one can make generalisations about the entire category of objects that the law refers to. It doesn’t matter whether hydrogen and oxygen is on Mars or in my office under the same conditions those elements will always behave in the same ways. Moreover, laws of nature are (at least approximately) true at any time and place in the universe. Thirdly, laws are used to predict facts about the world. Whether we have apples, chairs, cats or dogs falling from the sky, they will all – as objects of mass – obey the law of gravity in the same way. Secondly, candidate laws connect certain properties of objects without having to specify exactly what sort of objects they are. For example, by accepting Newton’s law of gravity, one can generalise that any object of mass m, which has a specific distance r to earth, will fall to the ground in a way that obeys that law. The first is that law-like statements make inductive inferences: they generalise from observed facts to unobserved instances.

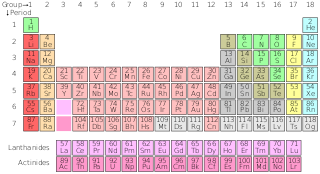

Source: © Shutterstock and © Science Photo LibraryĪs a universal law of nature, gravity affects cats, apples and other objects in the same way The nature of lawsĪll potential candidates for laws of nature have certain common features that are taken to be signs (though perhaps not sufficient criteria) of genuine laws. Examples from science that philosophers have examined as paradigmatic candidates include Newton’s law of gravity, the law of demand and supply, and the laws of thermodynamics. Now this should ring many bells for philosophers! As they attempt to understand the structure of the world, philosophers persistently ask whether there are laws of nature that govern the behaviour of things in the universe. 1 This term suggests that at least in chemical discourse the periodic table has a status that few classificatory schemes enjoy in science: it shows, to put it boldly, a law of nature. The periodic table is often mentioned in textbooks, chemical articles and popular texts as a representation of the so-called ‘ periodic law’. This is surprising not just because of its important role in chemistry. Where the periodic table has been disregarded though, is philosophy. It is an exceptionally handy tool, essential not just to chemical practice but also to the teaching of chemistry at all levels. By classifying chemical elements by increasing atomic number, chemists have discovered previously unknown elements, synthesised new substances and better understood the chemical and physical behaviour of matter. The periodic table is one of the greatest scientific achievements of all time.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)